ON THE ROAD - 35MM FILM PHOTOGRAPHY AND WRITING

for more of my 35mm film photos, click here

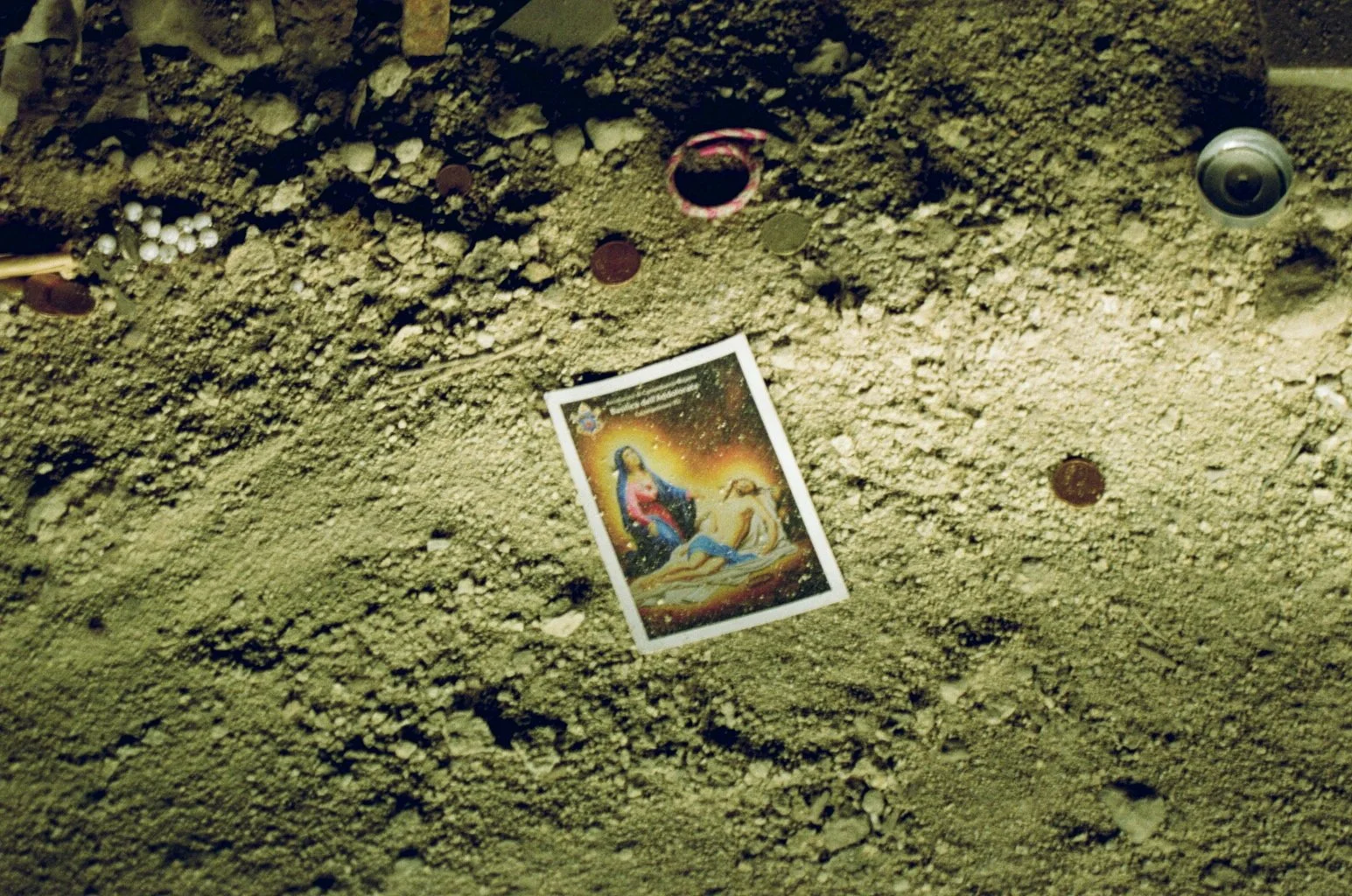

‘On the Road’ - The Not-So Divine Masculinity of New Age Travel Culture

I’m sitting in a hostel in Mexico, and the birds are singing while the men are musing. I’ve been traveling alone as a woman for three months now, so this scene is all too familiar. A group of late-20- to early-30-year-old, semi-enlightened, emotionally detached, Eckhart-Tolle-quoting, Birkenstocked men sit around in a soul-searching circle jerk, discussing the(ir) meaning of life and how they can totally get you the best weed you will ever smoke, man. My experience of the New Age movement is that it has become synonymous with man’s journey to self. I recently picked up a tattered copy of Jack Kerouac’s traveler’s rite-of-passage cult classic On the Road, and now I can’t help but see Kerouac’s protagonists everywhere I travel - from hostel to commune to farm to campsite - journeying down the road (once less, now more, due to Mexico becoming an anti-vax and gap-year haven) traveled. As I sit and write this article, I think of the book’s legacy sixty-six years later, and I wonder: who is this road for? On the Road is a story about Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, two young men navigating the open road of a hedonistic 1950s North America - the road from East to West and everything in between. The story is told by Paradise, but Moriarty is the one who captures all our attention. Moriarty is a traveler’s wet dream: he floats around the world doing everything and everyone; he is larger than life itself. For any traveler, or those longing to travel, the words send electric shocks through your system as you experience, perhaps for the first time, what it is truly like to be free. But here’s the catch - it’s nearly impossible to imagine the travelers in On the Road as anything other than men. And not just the protagonists, but all the waifs and strays they pick up along the way. The women characters that do exist are interchangeable wives, lovers, or mistresses - Moriarty ends up with three wives and constantly switches between them. In one chapter, Paradise asks a lover, “What do you want out of life?” “I don’t know,” she said. “Just wait on tables and try to get along.” She yawned. I put my hand over her mouth and told her not to yawn. I tried to tell her how excited I was about life and the things we could do together… she turned away wearily. In Kerouac’s world, men are frantic while women are static, men are searching while women are yawning. It seems that the women have given up on their lives before they even began. In truth, I can’t help feeling intensely jealous of Moriarty (and all his descendants). I want to float around Mexico, jump into strangers’ trucks, and sleep alone under starlit skies. I recently stayed at a nudist hippie camp full of men flirting with their divine masculinity. The camp reeked of gender essentialism, misaligned chakras, and German self-help gurus. One night, I ended up at a psytrance beach party where a well-respected community leader offered to give me a lift home after a fellow camper had come onto me unexpectedly. The community leader - of which community I am unsure, as it was definitely not Mexican but rather a transient New Age hippie gathering from lands far away - became my knight in shining armor, whisking me away from the beach party on his motorbike. We zoomed down the highway, the wind sweeping through my hair. Was this my Dean Moriarty moment, at 4 a.m. on the Oaxacan coast? Unfortunately not. The moment ended abruptly when I was ejected off the motorbike for declining to go back to his place, no longer worth his time. I had to walk home alone with a rock in my hand to scare off wild dogs. The next day, he led healing circles and spread words of wisdom. Soon after, a fellow traveler reminisced about jumping into a stranger’s van on the highway, who offered to take him to a party in the mountains - then seemed confused and even judgmental when I said I would be wary of doing the same alone. When poet Sylvia Plath wrote, “…my consuming desire to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, bar room regulars - to be a part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording… I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night,” it felt like she epitomized the frustratingly gendered experience of traveling: the desire to be a fly-on-the-wall, anonymous, contrasted with the reality that women are subject to the omnipresent male gaze wherever they go. Of course, times have changed since Plath wrote this note, but with the viral TikTok question, “Women - what would you do if there were no men on earth for 24 hours?” often answered with “walk around freely,” we can see that, as years pass, the same fraught relationship plays out between women and space, whether walking to the local corner shop or down the highway. My intention isn’t to victimize women travelers, or to put women (or any people who don’t fit that aforementioned traveler demographic) off traveling - quite the opposite. I want them to take up space from generations of Moriarty carbon copies. I want men traveling to make that space, to acknowledge that the Road narrative was written for them, and that their oblivion and detachment is not only annoying but harmful. I want the road repaved, and the story of travel rewritten. But that’s bigger than a plane ticket - it’s about changing who feels entitled to travel, who sees themselves reflected in the narrative, and who feels safe enough to journey. I’m sitting in a hostel in Mexico, and the birds are singing while the men are still musing. The birdsong crescendos, and for a moment it drowns out the soul-searching circle jerk. The group of men turn to me and ask what I think the meaning of life is. Their gazes fix on me as they wait patiently for what I am about to say. I open my mouth and… just kidding. They want a lighter.